Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein captures the heart of Mary Shelley’s masterpiece.

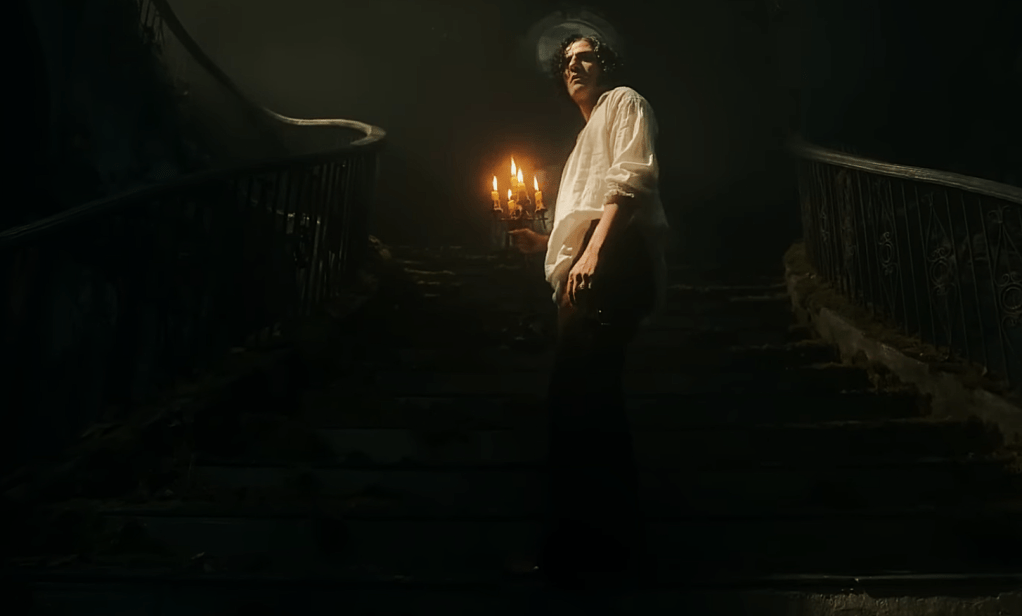

In del Toro’s hands, Frankenstein’s story becomes a reflection on the profound loneliness stitched into every human soul, the ache for acceptance and understanding that transcends era and genre. Where so many directors have settled for a gothic spectacle, del Toro lingers in the quietness of the horror, allowing the creature’s loneliness and Victor’s regrets to linger in the delicate candlelight. The film’s design is lush and, every shadow brimming with the possibility of new horrors or unexpected tenderness.

Much of the film’s impact rests on its cast. Jacob Elordi’s performance as the Creature is raw and deeply affecting. He embodies both the awkward innocence of a newborn and the tragic wisdom of someone cast aside too soon. His physicality communicates more than words ever could, making every gesture feel like a plea for connection. Oscar Isaac’s Victor Frankenstein, meanwhile, is portrayed not as a mad scientist but as a deeply flawed man driven by ego, fear, and longing.

Other standout performances include Mia Goth, who brings both fragility and fire to her role, grounding the film in human stakes even as the story spirals into myth and allegory. Del Toro has always been skilled at coaxing actors to embrace both the fantastical and the deeply human, and here he achieves some of the most nuanced performances in recent gothic cinema.

Del Toro’s visual design has always been one of his signatures, and Frankenstein is no exception. The world feels at once painterly and tactile.

It is not a spectacle for its own sake. Each detail serves the story. The stitched flesh of the Creature is not monstrous in the traditional sense; it’s tragic and almost tender. It’s designed to emphasize the fragility of life itself. Victor’s laboratory, full of instruments and decaying books, is less a space of triumph; it is in some way a grave of his obsession.

Del Toro’s Frankenstein is, at its molten core, a reckoning with what it means to be human, a question pulsing beneath the stitched sinews and haunted eyes of the Creature and pulsating in Victor’s fevered ambitions. In this telling, humanity is pieced together with contradictions. There is the capacity for both cruelty and tenderness, the terror of being misunderstood, and the fierce desire for a place to belong in the world.

The film asks us to contemplate the agony and beauty of consciousness. The Creature, cast out and reviled, learns language as a bridge to connect with others. Every word spoken, every gesture made, is a plea to be seen and known and a request for a place to belong. We watch as his longing grows into rage and then, heartbreakingly, into something like forgiveness. It is in these moments that del Toro’s vision is most piercing, reminding us that our humanity is shaped not by perfection but by our persistent, vulnerable search for meaning.

What makes this adaptation different from others is del Toro’s refusal to lean into easy horror tropes. Instead, he embraces ambiguity. To be human, the film suggests, is to stand in the ruins of our own creation and ask why we were made and whether love is possible despite the brokenness. The film’s closing scenes dwell in this uncertainty. There are no simple resolutions, only trembling hands and lingering questions.

This Frankenstein is both elegy and revelation. It forces us to see ourselves reflected in eyes that only want to be loved. It is a film that haunts because it speaks to something buried deep in the human condition, the loneliness and longing that never quite leave us.

By the time the final frame fades, del Toro has not just adapted Mary Shelley’s classic. He has resurrected it, infused it with new life, and reminded us why the story continues to endure after more than two centuries. In a world where adaptations often feel hollow or derivative, Frankenstein feels like both a return to origins and a new step forward. It is, in every sense, alive.

Streaming on Netflix November 7