Thrillers set in the cold share a certain feel to them. Snow mutes the world, the horizon looks endless, and there’s that cold feeling of loneliness and dread. Many of these stories fall into a certain category. Some are psychological, like The Shining; some are supernatural, like 30 Days of Night or The Thing; some are pure survival, and some are detective puzzles. Dead of Winter doesn’t sit still in any one category. It borrows the patience of a survival tale, the nerves of a crime story, and the uneasiness of a psychological yarn, then turns all of that into a striking human fight against the elements and the worst in people. From its first whiteout frame, the movie keeps the air thin and the choices sharp.

“Dead of Winter” opens with a simple terror. A lone driver grips the wheel as heavy snow swallows the road. The wipers thump, the wind howls, and the world shrinks to a tunnel of white. Director Brian Kirk sets his tone right there. This is a thriller built on coldness, isolation, and choices made when no one else is coming.

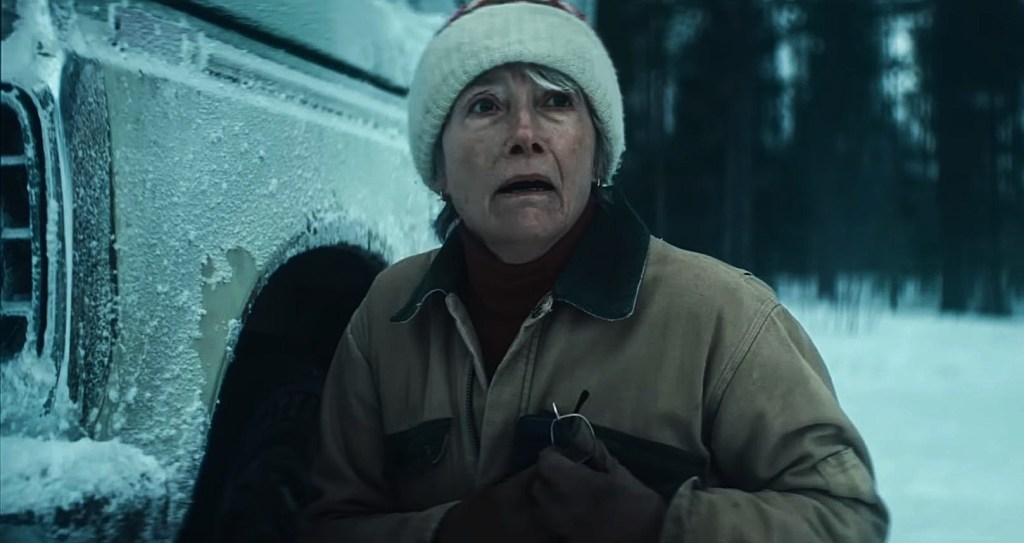

Emma Thompson plays Barb, a widow who heads to a remote Minnesota lake to scatter her husband’s ashes. Thompson leans into everyday strength rather than movie hero bluster. Barb is practical, stubborn, and careful. She knows how to read ice, how to work a heater, and how to keep moving when the cold tries to slow her down. Thompson makes that competence cinematic. You feel safer when she is on screen, even as the danger closes in.

The film’s key trick is how it uses the landscape to push the story forward. Finland stands in for northern Minnesota, and the mismatch never matters. The widescreen frames hold a lot of sky and a lot of white, with cabins, trucks, and the tiny square of an ice shanty swallowed by the horizon. There are few hiding spots. When a rifle cracks or boots crunch across crusted snow, the sound carries. That stillness becomes a suspense machine. Kirk is patient about this. The groan of shifting ice does as much work as the score.

Barb’s path crosses with a married couple played by Marc Menchaca and Judy Greer. He is taciturn and wary. She is wired, impatient, and very dangerous. Their cabin is more trap than home, and what Barb finds in the basement is enough to pull her into a rescue she did not plan for and cannot ignore. The plot from there is straightforward. A chase forms across woods, frozen water, and claustrophobic rooms. People make bad choices because the weather, fear, and pain are shrinking their options by the minute.

It is a pleasure to watch Greer switch lanes. Known lately for warmth and dry comic beats, she hits a jagged frequency here without turning the role into a cartoon. Her character believes she is on a mission and refuses to slow down for anyone else’s reality. Menchaca plays the flip side, a man who looks built for menace and then shows seams and doubts. Neither villain is mysterious for long, but they are human enough to keep you uneasy. Laurel Marsden, as the abducted young woman, has the hardest job. She spends long stretches bound, terrified, or muffled, yet finds small beats of defiance that give her more than victim shading.

Thompson’s work holds the center. She underplays Barb’s grief and lets it leak out through routine. A gloved hand resting on a tackle box says more than a speech. When violence finally finds her, she reacts like a person who has weathered real loss and refuses to invent drama where focus is needed. The movie asks her to do quiet problem solving, awkward fights, and one wince-inducing field dressing. None of it looks elegant, which is the point. She is not a marvel. She is a capable adult who understands that cold, time, and shock are enemies you cannot negotiate with.

Christopher Ross shoots the snowfields with nearly monochrome restraint, then lets sparks of red or the purple of a parka pop like warning lights. Volker Bertelmann’s score starts with distant synths and grows into pulses and strings when the chase accelerates. The cutting stays clean. You can follow who is where, which matters when everyone is bundled into bulky layers and the horizon never changes.

There are bumps. The film leans on sunny flashbacks to Barb’s marriage to explain why this lake matters. Those memories are sweet and are helped by Gaia Wise playing the younger version of Barb, but they pause the momentum during the middle stretch. The story also relies on a few convenient items that appear when needed and on the kind of bad decision that keeps thrillers moving. A villain leaves a weapon behind at the wrong moment. A vehicle stalls at exactly the right time. None of it kills the tension, though a tighter script would have found cleaner ways to reach those turns.

The accent work will be a conversation starter. Thompson’s Minnesota vowels shift a bit from scene to scene. It is never distracting enough to pull you out of the film, and the exaggeration reads as part of the character’s effort to be friendly in a place that defines itself by neighborly politeness. If anything, the voice becomes a reminder that kindness does not cancel steel. Barb can say please and thank you and still cut a hole in the ice for someone who needs to be stopped.

What gives “Dead of Winter” a pulse beyond its genre comforts is the decision to let two middle-aged women drive the conflict. We get a hero who measures success in small, decisive acts and an antagonist who believes the world owes her a fix. Their showdown plays differently than if the roles were filled by stoic men. It is not softer. It is more personal. Each woman demands control in a place that punishes overconfidence. When their paths finally cross on the open ice, the stakes feel earned because the movie has been honest about the limits of flesh in deadly cold.

At ninety-plus minutes the film stays true to its own scale. The action never grows into spectacle. Fights are clumsy, weapons are heavy, and the environment wins most arguments. That humility lets the final passages land with a mix of dread and catharsis. The movie does not need a twist to feel complete. It needs the right choice from a character who has earned your trust.